The recent inclusion of hundreds of mainland China-listed companies into the MSCI Global Emerging Markets Index means money managers are now obliged to invest in companies many know little about. In most cases targeted investigative research will be the only way of avoiding major landmines. Now forced to set foot in China, investors will need to watch their step.

On June 1, index-maker Morgan Stanley Capital Index (MSCI) added 234 Chinese large-cap firms to its emerging market tracker, the first time a major index has included yuan-denominated Chinese stocks. The move will lead to unprecedented sums of foreign capital pouring into China’s Shanghai and Shenzhen bourses.

Funds and investors who track MSCI’s widely-followed index will now be forced to buy shares in little-known Chinese companies. Many hedge fund and institutional investment clients, including some of the world’s largest capital allocators, have expressed concerns publicly and in private over the challenges now facing fund managers obliged to invest direct into China’s domestic securities market. These challenges include weak corporate governance, a lack of transparency, and an inconsistent regulatory and legal enforcement environment. Yet despite the risks, investors who can take advantage of local knowledge and do their homework will also be able to reap significant rewards.

How Big is the Opportunity?…

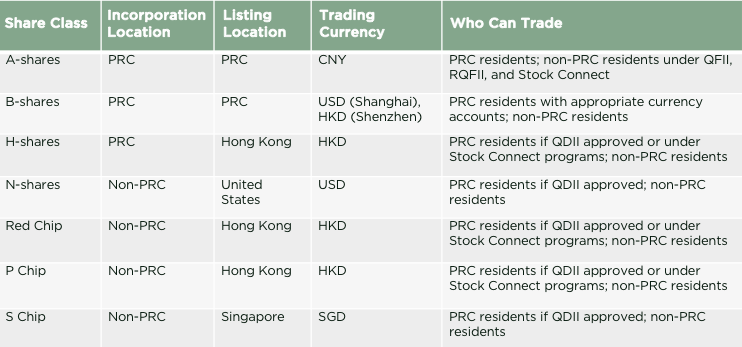

China’s equity market is worth $8.7 trillion, according to a 2017 World Bank report¹. The market is divided across an alphabet soup of share classes, including A, B, H, and P-shares, among others. (See inset table for descriptions.)

The companies that have joined the MSCI index are all drawn from the A-share rolls, which are Renminbi (RMB) denominated shares of Chinese-incorporated companies trading on the Shanghai and Shenzhen stock exchanges. These domestic shares can be traded by residents of the PRC or by investors outside China under exemption rules such as the Qualified Foreign Institutional Investor (QFII), Renminbi Qualified Foreign Institutional Investor (RQFII), or Stock Connect programs.

As of April 2018, more than 3,500 A-Shares were listed on the Shanghai and Shenzhen stock exchanges, representing all industries and sectors. High volatility over the past few years makes it difficult to calculate the total market capitalization for A-shares—over the past year, the total market cap of A-shares traded on the Shanghai Stock Exchange has ranged from about USD 5 trillion to 6 trillion—but the overall trend over the past two years has been a steady rise.

In addition to A-shares, many other classes of shares trade in China or are relevant to Chinese investors. These are described in the table below, although only the A-shares are yet in play as part of the MSCI index decision.

MSCI is an independent provider of portfolio risk analysis tools. It runs hundreds of indices of public equities, including its flagship All Country World Index (“ACWI”), which comprises 2,400 companies across 11 sectors and serves as the industry standard for measuring global stock market activity.

MSCI has added China A-shares to three of its indices: the ACWI, the China Index, and the Emerging Markets Index. The 234 A-shares it has included are all large cap stocks, drawn from various sectors. As of their June inclusion, China A-shares represented 0.39% of the MSCI Emerging Markets Index. In August, the adjusted market capitalization of China A shares is set to increase, bringing them to 0.78% of the MSCI Emerging Markets Index.

… and What are the Risks?

Thanks to a series of high-profile frauds and blow-ups, often catalyzed by well-publicized attacks from short sellers, the challenges associated with investing in Chinese public companies have become well known. Most infamous among them is outright fraud.

This was the case in the brazen 2009 theft of Puda Coal, whose Chairman transferred ownership of the company’s most valuable assets to himself and unloaded them before selling more than $100 million worth of the denuded parent company’s shares in the United States. It happened again in 2011 when Canadian-listed Sino-Forest Corporation drastically overstated the number of trees it actually owned, and was ultimately called out in dramatically public fashion. But extreme cases of blatant fraud are not the only challenges associated with investing in Chinese companies.

A dearth of reliable corporate and market data also presents difficulties. Information that investors typically rely on when evaluating profitability or addressable market size does not always exist in the same quantity or format in China as it does in other markets. Disclosures by companies can be incomplete, and investors who lack local expertise can be ill-equipped to acquire for themselves the information they lack. For instance, consolidated financial statements can lack the granularity that investors need to accurately evaluate earnings quality and predict future business growth. And analysts accustomed to conducting financial analysis in North America and Europe don’t always know how to appropriately weigh China-specific factors such as changing regulations and the particularities of regional and province-level operating requirements.

Changes in Chinese corporate governance add an additional layer of uncertainty. The involvement of Chinese Communist Party cells within Chinese companies had been waning in recent years but is on the rise again due to recent reforms designed to deepen the Party’s role across Chinese society. Beijing is increasingly mandating that these cells play a role in operational decision-making in both state-owned enterprises and foreign joint ventures. What this will ultimately mean for corporate governance, capital allocation decisions, and shareholders’ rights remains to be seen, and this uncertainty can cause skittishness, especially among international long-term investors.

Muck or Brass?

The risks particular to investing in China are real and cannot be ignored, but risks beget their own opportunities. Obviously, not all of China’s 3,500 plus listed A-shares are frauds. Within this group, good companies exist, and opportunities to own and trade them can complement a wide variety of investment strategies. The key for investors is filling the information gaps and mitigating the China-specific risks. For those able to do so, the information asymmetries can become a source of significant uncorrelated returns.

Blackpeak is the market leader in researching Chinese listed companies, and we help some of the largest institutional investors and hedge funds navigate specific investment risk in listed equities in China. Since the Sino-Forest saga in 2011, we have researched for our investment clients practically every major China-listed company publicly attacked by short sellers, and many more that have never been exposed. In some cases, we have verified the “short” claims; in other cases, we have debunked them.

In our experience, a number of basic screens will help to flag many—albeit not all—problematic companies, particularly from a possible integrity, governance or fraud perspective (see table for a non-exhaustive list). We apply many such screens to the listed company research we undertake for our investment clients. We flag up major issues or concerns that we find, then we work with these same clients to refine our research and go deeper. We add value by answering sophisticated questions relating to our clients’ fundamental investment case, typically by collecting hard-to-find information about operations, the competitive landscape, supply and distribution chains, customer sentiment, regulatory requirements, pricing and margins.

Blackpeak works within a strict compliance framework to acquire information that clients can incorporate into their analysis without putting at risk their ability to trade. We have undertaken bottom-up research to help our clients understand some of the highest-profile listed firms in China, collecting differentiated information to corroborate or challenge long and short theses.

We have experience conducting surveys to understand customer sentiment and distribution processes. We have carried out complicated channel checks to elucidate information about supply chains and investigate possible accounting irregularities, and have observed factory operations to assess operational realities.

No plans have yet been announced to add other A-shares to the MSCI beyond the first tranche of 234, but such additions are inevitable. Other large index providers will watch the results of MSCI’s decision closely and will have to add A-shares to their own baskets (as many China-specific indices already do) if the MSCI move is successful. The inclusion of the first A-shares in the MSCI signals a growing acceptance by investors of Chinese companies in the mix of investable assets as well as the inevitability of their inclusion given the sheer magnitude of China’s domestic stock markets. Institutional investors and their wealth management clients are increasingly expecting Chinese firms to be a part of their portfolios. Which China stocks are added to a portfolio and which left out will play an increasingly important role in driving Alpha.

疑惑深,智慧深;疑惑浅,智慧浅: Deep doubts, deep wisdom; small doubts, little wisdom.

¹Market capitalization of listed domestic companies (US$), World Federation of Exchanges Database.

Further Reading

For a comprehensive assessment of the current state of corporate governance in China, we would highly recommend the recently-published White Paper by the Asian Corporate Governance Association, entitled, “Awakening Governance: The evolution of corporate governance in China”. It can be downloaded free of charge here: https://www.acga-asia.org/specialist-research.php