The EU has been tightening regulatory scrutiny of Chinese inbound investment over the last three years. The implementation in April 2019 of a new EU-wide framework for reviewing acquisitions intensifies the trend of already-declining Chinese FDI in the EU and high-profile blockages of deals there since 2016. Currently facing trade tensions with the US, Chinese investors may now find that the EU also presents an increasingly complicated political and regulatory environment.

What is the European FDI Screening Framework Regulation?

In April 2019, a new EU-wide framework, called the European FDI Screening Framework Regulation, went into effect. This Framework calls for member states to share information with, and require information from, other members on specific FDI deals. Member states and the European Commission are also allowed to issue non-binding opinions to one another if the FDI deal in question relates to the public order and security of the EU. The list of sectors earmarked for scrutiny under the Framework includes energy, transport, robotics, finance, health, and media. The Framework also asks member states to pay special attention to transactions in which the foreign investor is linked to a state-owned enterprise (SOE) or if an investment between EU countries has an ultimate owner outside the EU.

The Framework emphasizes communication and cooperation, but the final decision to allow a transaction to pass is ultimately at the sovereign state’s discretion. However, that state must justify any decision that goes against the opinion publicly issued by the EC. While there have not yet been any high-profile test cases of the Framework, these new requirements reflect growing concerns among EU leaders about the national security implications of Chinese investment in particular. They are likely to make investments by Chinese companies much more politically challenging and could even trigger sharper political conflict between EU states over proposed Chinese deals.

The EU Initially Receptive to Chinese FDI

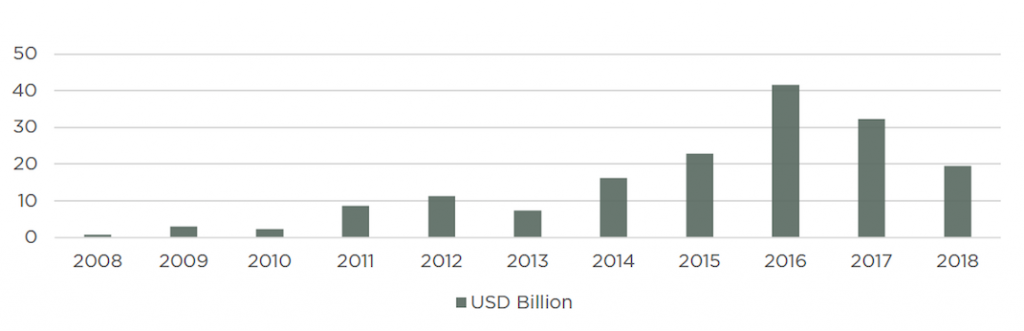

After the 2008 global recession and the 2010 Euro crisis, European countries, especially in southern and eastern Europe, welcomed Chinese investments as a much-needed source of capital. This trend saw a peak in 2015 with ChemChina’s acquisition of the famous Italian tiremaker Pirelli for a record USD 8.8 billion. In fact, Chinese FDI in the EU soared from just USD 789 million in 2008 to a peak of USD 42 billion in 2016 before plummeting to USD 19.5 billion in 2018. This recent decline, driven largely by China’s own imposition of strict capital controls, is also likely due to the increased regulatory scrutiny in the EU.

The symbolic turning point occurred in 2016 for two reasons. In that year, Chinese FDI into the EU surpassed EU outbound FDI into China. This shift prompted European regulators to begin to reassess trade relations with China. Many argued that the Chinese government unfairly limited access for European firms in a variety of sectors and that informal discrimination continues against foreign companies – restrictions that Chinese companies did not face in Europe. Also in that same year, the Chinese appliance maker Midea Group acquired Kuka, a leading robotics manufacturer in Germany. The Kuka acquisition instilled an anxiety in many European countries that critical national technologies and strategic sectors were now at risk of being transferred to China. This transaction marked a turning point in assessments of Chinese FDI by Germany, the EU’s largest economy, and ultimately led both to the creation of the new Framework and the strengthening of other national security-focused FDI regulation.

Steps Toward EU-Wide Screening Regulations for FDI

Kuka provided a lesson for Germany: the reason the government could not step in to stop the deal was that high tech firms were not legally considered a strategic sector. After the Kuka deal was completed, Germany moved in 2017 to approve new rules that allow the government to examine and block the sale of an expanded list of strategically important sectors to foreign investors. This list now includes transportation, energy, telecommunications, defense, and software firms. Since December 2018, Germany will also review any deal in which a non-EU company is proposing to buy a stake of at least 10%.

These new regulations enabled the German Cabinet to block the Chinese acquisition of a German company in 2018 for the first time when Chinese metal manufacturing firm Yantai Taihai sought to acquire Leifeld Metal Spinning, a German heavy metal manufacturing firm that produces metal for the auto, aerospace, and nuclear sectors. Yantai Taihai holds extensive connections with China’s nuclear sector and provides smelting and metal processing services for the country’s nuclear power market. The prospect of critical technology transfer to China prompted the German government to launch a month-long investigation and eventually veto the acquisition. This decision came even after Yantai Taihai had withdrawn its bid to avoid being the subject of Germany’s first ever veto. Taken alongside its earlier calls for “reciprocity” from China, the German government sought not only to protect its key industries, but also to send a strong message regarding its perception of the uneven playing field for German firms in Chinese markets.

Meanwhile in November 2018, France expanded the list of sensitive sectors in which foreign investments are subject to review and approval to include cybersecurity, artificial intelligence, robotics, and aerospace. The French government has also moved more directly to protect what it sees as critical technology from being acquired by Chinese companies. Most notably, in July 2017, France temporarily nationalized its biggest shipyard STX France in order to block a bid from Italian firm Fincantieri. This was reportedly at least in part due to fears that state-backed China State Shipbuilding Company (CSSC) might be able to access its technology through a joint venture CSSC had with Fincantieri. STX is also France’s only shipyard capable of producing military ships. The French economy minister claimed publicly, however, that the deal had been done to protect French citizens from job losses.

Aside from blocking certain Chinese investments within their own borders, it is not unprecedented for an EU country to try to restrict Chinese FDI in another member state. For example, in May 2018 the Chinese SOE China Three Gorges (CTG) submitted a USD 10 billion takeover bid of the Portuguese electric utilities firm Energies de Portugal (EDP). The potential transaction incited backlash in the EU. Two Portuguese and German members of the European Parliament wrote a letter to European Commission President Jean-Claude Juncker expressing concern about the CTG bid, saying that allowing it to pass “neglected the negative impacts FDI might have on critical and strategic infrastructures of a Member state…and hence, the impacts for the EU as a whole.” Juncker replied that the European Commission did not have the legal instruments necessary to step in at the time. The CTG bid died a slow death partly because its price was seen as low and the company missed several regulatory filing deadlines. This is precisely the kind of transaction the Framework was created to handle, and would have forced Portugal to respond more directly to these concerns had the Framework been in place.

Continuing Divisions

The Framework is the most recent development of a deeper European trend of scrutinizing Chinese FDI. Yet even though the Framework passed in the European Parliament with an overwhelming majority of 500 votes to 49 against and 56 abstentions, differing opinions remain among EU member states on how stringent FDI screening should be. The push for the Framework mainly came from western European countries that have historically been the largest recipients of Chinese FDI: France, Germany, Italy, and the UK. On the other hand, Nordic and Benelux countries have aligned themselves with eastern EU countries that still view Chinese FDI as an important source of investment.

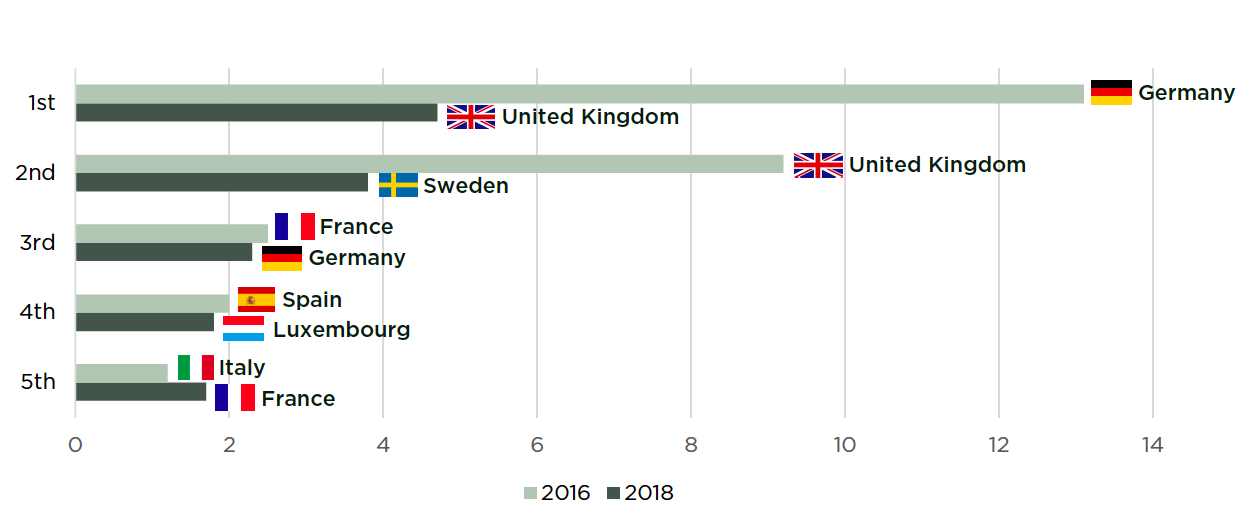

The Nordic and Benelux countries in particular stand to become new major destinations for Chinese FDI. The “Big Three” EU FDI recipients – France, Germany, and the UK – were no longer the most preferred markets for Chinese investors in 2018. While the UK remains in first place, Sweden is now the second largest recipient of Chinese FDI in the EU, with USD 3.8 billion received in 2018. The majority of this figure is from the USD 3.3 billion investment from the Chinese automobile manufacturer Geely in the Swedish car company Volvo. Germany has dropped to third place, while Luxembourg has risen to fourth place at USD 1.8 billion in 2018. This figure is mainly attributed to the USD 1.6 billion acquisition by China’s Legend Holdings of the Banque Internationale de Luxembourg. France, previously in third place, is now the fifth largest recipient. Finland has so far been a significant recipient of Chinese FDI in 2019, with a USD 5 billion investment with China’s ANTA Sports purchase of Finland’s Amer Sports.

Indeed, though these new major destinations of Chinese FDI have much smaller populations than the Big Three, the ease of entry and lack of scrutiny in these relatively less populous countries have attracted considerable Chinese investment. Furthermore, Chinese investors in 2018 have diverted their focus more toward finance, technology, and auto production – key sectors in northern Europe – rather than infrastructure, transportation, and utilities compared to previous years.

Looking Forward

The EU now poses more complications for Chinese investors. Even after the Framework was passed earlier this year, the European Commission labeled China a “systemic rival” in a strategic proposal mapping out relations with Beijing. High-profile European officials even called for the EU to implement veto power over investments from China. Yet on the EU-wide level, the Framework is unlikely to cause the same challenges that Chinese investors face with the Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States, a government committee that can completely block potential investments. For now the Framework remains non-binding, and the veto proposal does not appear to have any real traction. Overall, while there are increasing challenges in the EU, they do not rival the intensity of the US-China trade war.

Figure 1: Annual Value of Completed Chinese FDI Transactions in the EU-28

Source: Rhodium Group

Figure 2: Top 5 EU Destinations of Chinese FDI in 2016 and 2018, USD billion